With an estimated 8.7 million species on the planet, a robust system is needed to name, describe and organise so many life forms. For this task, biodiversity relies on taxonomy, a system that helps to identify and study species so that we can recognise and conserve them.

Why organise and classify living things into species, genera or families? Because with so many living things in the world, it would be immensely confusing, particularly in scientific articles and communications, if there were no uniform and globally accepted methodology to help organise and classify them. Taxonomy is the science that names, describes and organizes life forms on Earth.

The word ‘taxonomy’ was coined by Swiss botanist (and taxonomist) Augustin de Candolle (1778-1841) and derives from the Greek taxis, which means to order or organise, and nomos, a term which means to make into a convention or law.

Taxonomic organisation is a hierarchy so that each group of living things is classified within progressively larger groups or categories, until the last group encompasses all life on Earth. In addition to systematically organising all known organisms, this system also gives an idea of the evolutionary relationships between them.

The main taxonomic categories are: species, genus, family, order, class, phylum or division, kingdom and domain. In other words, a species belongs to a genus (which may contain one or more species), which in turn is included in a family (which may also have one or more genera) and so on until we reach the highest taxonomic category.

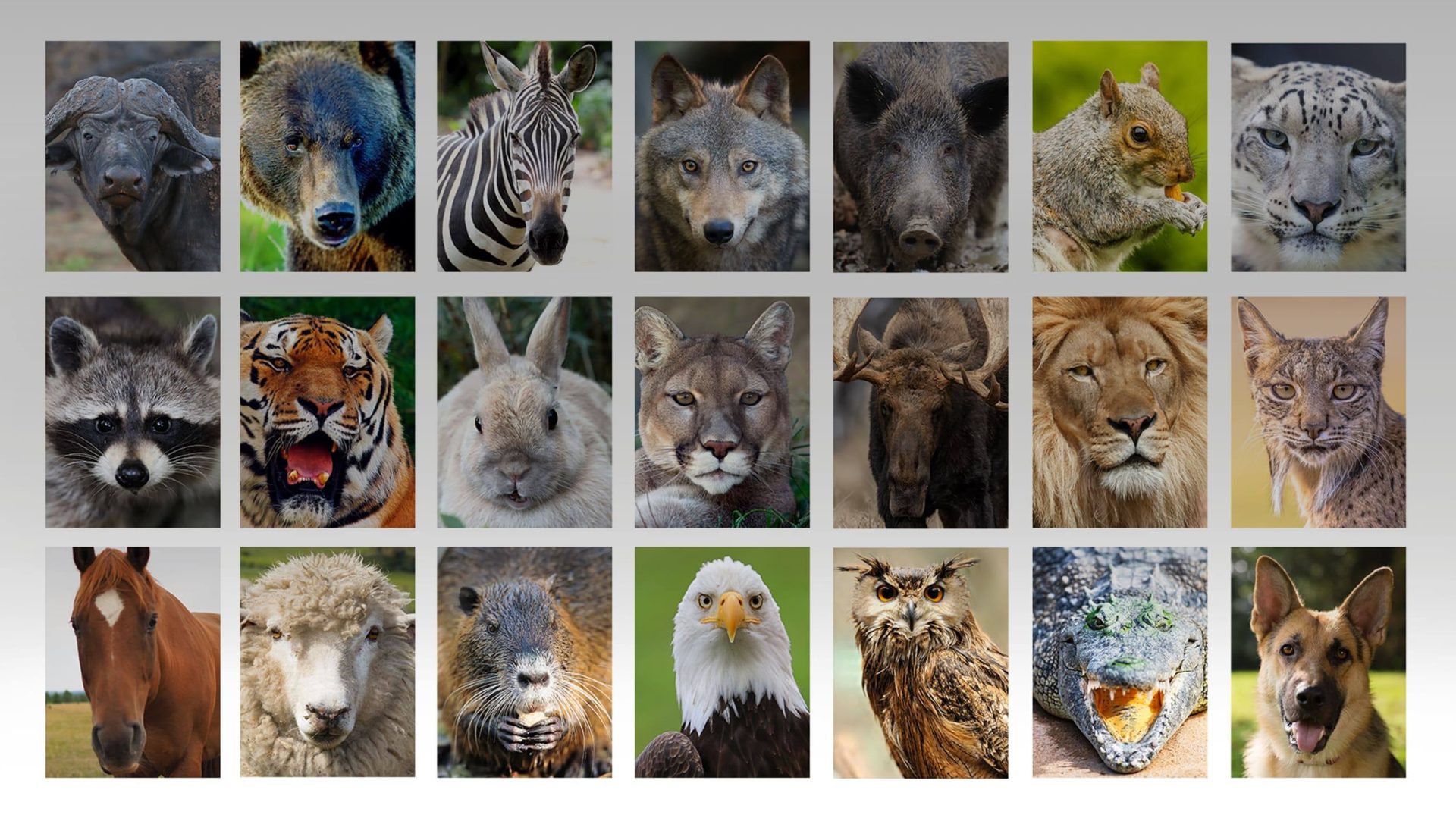

Let’s take the wolf as an example:

- Species: Canis lupus (includes only the wolf and its various subspecies, including the Iberian wolf);

- Genus: Canis (includes the wolf and the domestic dog, for example);

- Family: Canidae (includes animals such as the fox and the coyote);

- Order: Carnivora (includes all carnivorous mammals, from the genet to the bear);

- Class: Mammalia (includes all mammals);

- Phylum: Chordata (includes animals, such as fish, reptiles, birds, etc.);

- Kingdom: Animalia (includes all animals, from insects to mammals);

- Domain: Eukaria (includes all eukaryotes, i.e. organisms with an organised nucleus, where the genetic material is surrounded by a membrane).

But if a common name already exists, why are scientific names used and what is the reason for using them in a language different from our own? Although there are numerous common names, especially for species with a large area of natural distribution, these names are very variable: they change from language to language (between countries) and region to region (even within the same country).

One example of the latter case can be found in the plant Ruscus aculeatus (Butcher’s broom), which in Portugal alone is known by at least four common names: gilbardeira, falso-azevinho, vasculhos and pica-ratos. With so many names, confusion may arise when referring to the species, and this confusion is even greater between different languages and countries.

This explains the importance of scientific names: unique names composed of two parts (binomial nomenclature); each name refers only to a given known species, standardising the nomenclature of a living being throughout the world. Returning to the previous example, the Latin name Ruscus aculeatus is the same in Portugal, Argentina, Japan or anywhere else in the world and refers to that plant species only.