Eight native species of oak trees are usually described in Portugal, but the analysis of molecular data is rewriting the history of Portuguese oaks, says botanist and researcher Carlos Vila-Viçosa.

Determining the species or subspecies of a given living being has historically involved the analysis of its observable characteristics – physical forms, distribution area, ecology, or bioclimatic zone, for example. The concept of species and subspecies has therefore involved a high degree of subjectivity that can now be reduced thanks to new knowledge and technologies that range from genetics to information technology.

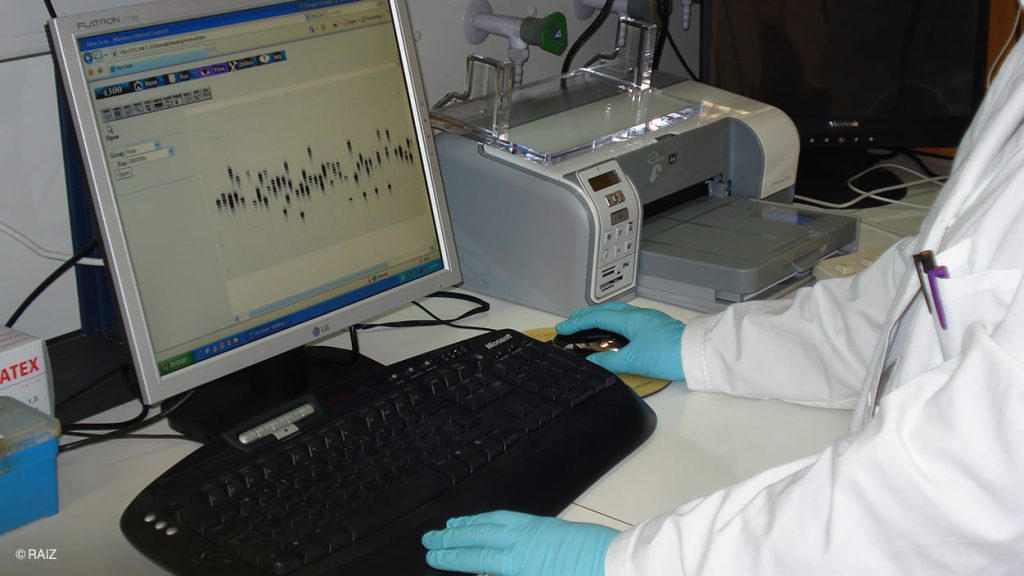

This is what Carlos Vila-Viçosa, botanist and researcher at CIBIO-InBio, Museum of Natural History and Science of the University of Porto and Biopolis, has been doing for a long time. He has long been dedicated to getting to know the trees and shrubs of the Quercus genus (common oaks, cork oaks, and similar), in particular those native to the Iberian Peninsula, including the Portuguese oaks. Together with other Portuguese and Spanish botanists and ecologists, he is using the analysis of molecular markers (markers in the DNA, where the unique characteristics of each individual and hereditary features are encoded) to describe them. And these objective data are telling a different story about several Portuguese oaks.

“Our data show that there is such a large molecular divergence between certain species and what were until now considered their subspecies, that the subspecies have to be re-classified as species”, says Carlos Vila-Viçosa, giving as examples Quercus estremadurensis and “our” Common oak from the Minho region and the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula – Quercus broteroana – both traditionally classified as subspecies of Quercus robur.

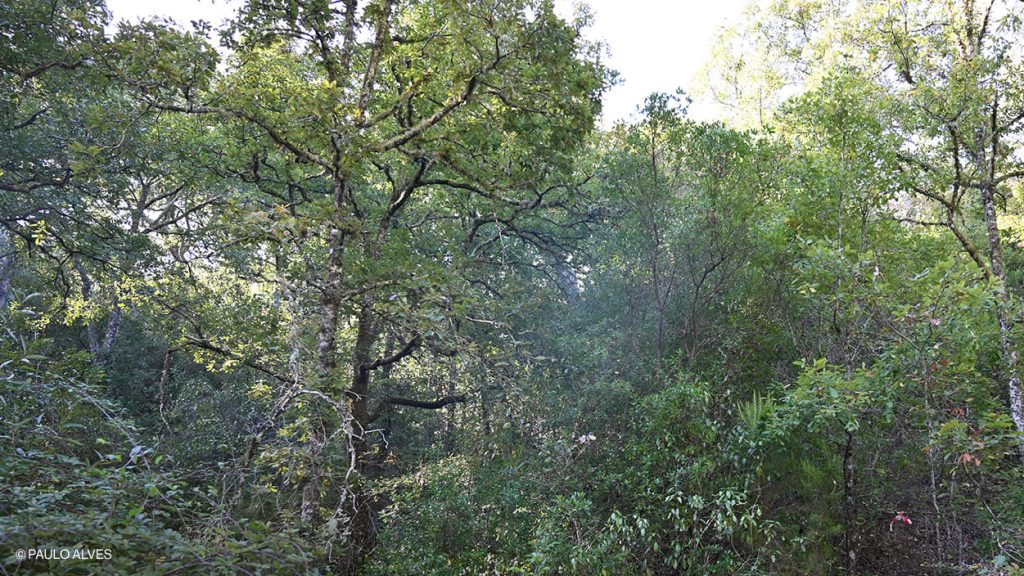

Field and laboratory work has also revealed new hybrids: “we observed 23 hybrids, three of which had never been discovered in the wild in Portugal”. One of them, for example, is the result of a cross between Lusitanian oak (Quercus lusitanica) and holm oak (Quercus rotundifolia) and will be named Quercus x alvesii, “in honour of the work of Portuguese botanist Paulo Alves”.

The discoveries have been shared with the international scientific community in articles and conferences for some years now, but changing established canons is not easy and takes time.

As Carlos Vila-Viçosa says, in the 1930s, German botanist Otto Schwarz (1900 – 1983) had proposed changes in the then current taxonomy of the Iberian Quercus and even new species – namely, Quercus estremadurensis, which he observed in the areas of Sintra and Coimbra. But being a foreigner questioning the Iberian authorities on the matter, his theories were rejected. French botanist Aimée Camus (1879 – 1965) considered it a subspecies, and her proposal was accepted, despite the criteria being poorly supported. “Often, writers referred to hybrid groups or arbitrarily assigned subspecies to specific bio-geographical areas”, explains the researcher.

It should be noted that the extensive hybridization between different oaks is one of the factors that, throughout history, has made taxonomic classification difficult. Another is the high morphological plasticity of the species of this genus, with the existence of ambiguous characteristics – for example, different shaped leaves on the same tree.